When I started this Substack a year and a half ago and named it “The Art of Losing,” I was mostly thinking of Rafael Nadal. I was so inspired by the intensity he brings to competition versus the grace and equanimity with which he handles losing. I love a big-feeling person. I love watching emotion take over someone’s whole body. Right now I’m thinking of my younger son. But typically, this kind of—hmm, how shall we call it?—passion comes at a price.

But not so with Nadal. When Rafa won a crucial point, he’d explode with a bended-knee-multiple-air-punch, but then, fascinatingly if the match didn’t go his way, he’d calmly press his lips together and shake his head as he slipped off his sweaty headband. He’d approach the net with an outstretched hand and kindly accept defeat. I don’t know of another top athlete like that, though I’m sure they must exist.

This kind of emotional discipline makes me think of a line from the author and Jungian analyst, James Hollis: “What good works flow from the suppression of our strong feeling life? Where does that natural energy go…?”

Only those closest to Nadal can know! (I bet his wife has a theory and/or opinion.)

But what I’m really trying to say is that the athletes who respond to losing with tantrums—by throwing their rackets, shouting at the refs, charging the mound—they make so much more sense to me. Historically, I’ve been a horrible loser, and perhaps ironically, if I was able to show any equanimity at all during one of my kids’ tantrums it was because I related to them so much in those moments. Part of me had been there, wanted to go there still.

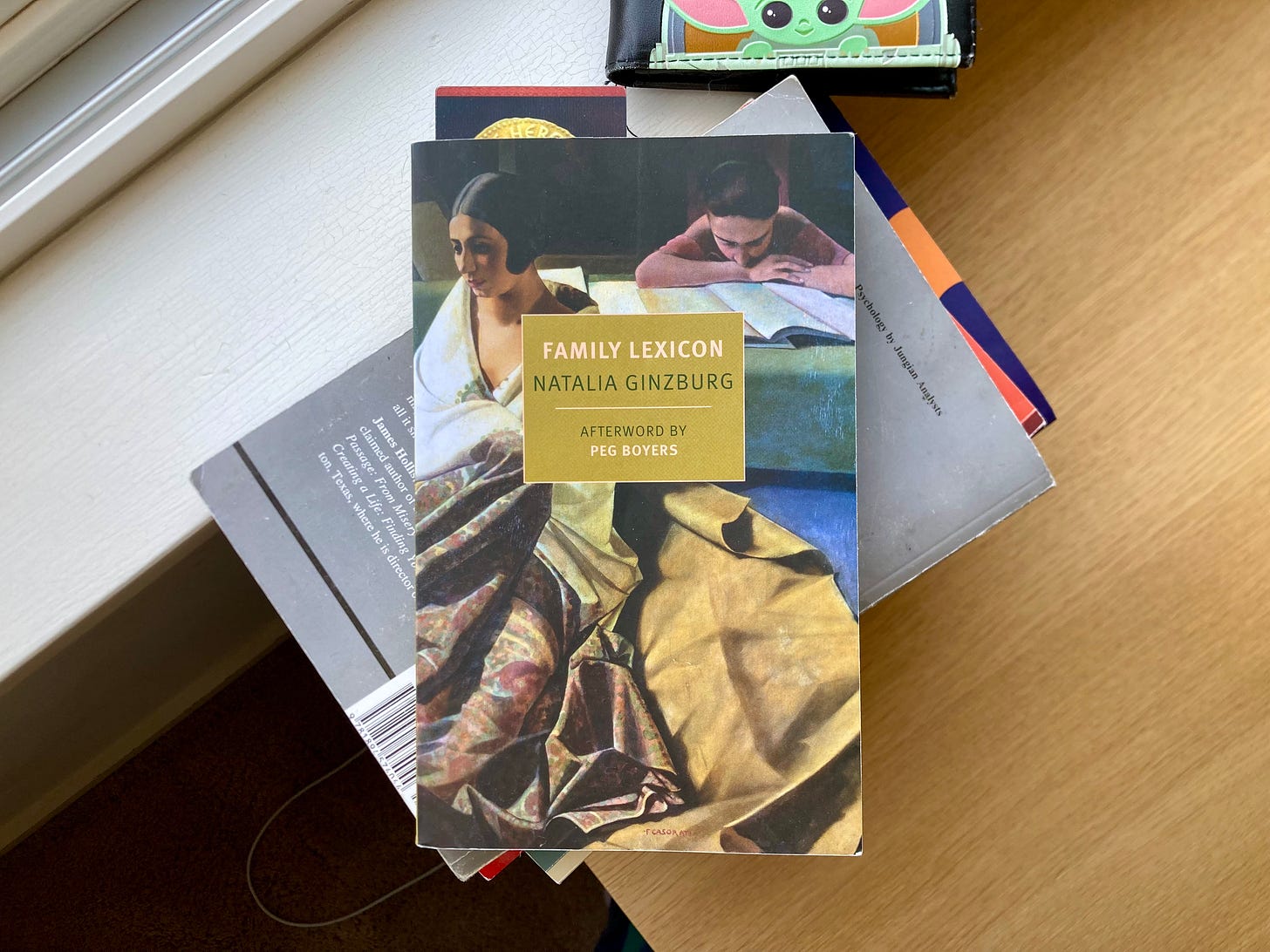

Which brings us to election night, when… I didn’t have one. A tantrum, that is, or even an outburst. (Which was how I responded in 2016.) Instead, I turned off the talking heads and opened up Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon.

I only had about thirty pages left and I was craving Ginzburg’s world, which is really saying something because the book is a memoir and takes place largely during Mussolini’s Italy, WWII, and what Ginzburg refers to as “the racial campaign.”

But the specific timeline of events are never super clear; Ginzburg doesn’t give many dates and, like in a novel, she jumps around chronologically.

At one point, before the war, her brother Mario is arrested for distributing antifascist materials on the Swiss border. Then, the following day, Ginzburg’s father is arrested via his presumed association with his son.

It’s dramatic for sure, and rereading that section of the book just now, it’s not like Ginzburg undercuts the terror of that moment in their lives, but in the way she recounts her mother Lidia’s fear and uncertainty, there is a kind of comforting continuity. Her mother has an almost irrepressible joie de vivre even in the worst of times, and as the family is scrambling for ideas on how to get Beppino—the dad’s nickname—out of jail, Lidia travels to Rome to visit a specific, connected antifascist. Of this trip, Ginzburg writes:

My mother returned from Rome more terrified than ever. She’d nevertheless had a good time in Rome because she always liked to travel.

It’s a tiny moment, but the whole book is like this. Bad things are happening and yet, other things are too. Maybe there was time for gelato? Maybe she glimpsed the Colosseum and was uplifted by its architectural heft?

But whatever happened in Rome, the feeling-tone remains: it’s all mixed up. The terror and joy. The cruelty and care.

I particularly grew to love the father character—Giuseppe slash Beppino, depending—or if not him exactly, I grew to love the way Ginzburg writes him. So much so that I’d almost forgotten how horribly he comes off at the beginning. Would I have forgotten completely if the translator’s “Notes” didn’t start immediately opposite the last page of the book so that I was reminded of the hole Ginzburg digs herself—in terms of Giuseppe’s likeability—on the very first page?

She writes:

[My father] was very harsh in his judgments and thought everyone was stupid. For him someone stupid was a “nitwit.”

Okay. Not great. But then one paragraph later, it gets much worse:

In addition to the “nitwits,” there were also the “negroes.” For my father, a “negro” was someone who was awkward, clumsy, and fainthearted… Any act or gesture of ours he deemed inappropriate was defined as a “negroism.”

If I’m being honest, I struggled to get through the first twenty-some pages. I didn’t really want to read a memoir about a domineering patriarch who terrorized his family. But probably because prior to this, I’d heard such good things about Natalia Ginzburg and probably because it’s one of these NYRB “Classics” and I usually like a NYRB Classic and probably also because I knew Ginzburg was half-Jewish and had lived through WWII… I kept reading.

I think Giuseppe started to change for me on page thirty-one when Ginzburg describes his obsession with the mezzorado, which was basically yogurt before yogurt was available to purchase at stores and therefore he had to make it himself.

My father always woke up at four o’clock in the morning. After getting out of bed, his first concern was to go and see if the mezzorado had turned out well.

Spoiler: it often hadn’t! And Giuseppe was mad about it! I think what happened was that I began to get a feel for his outbursts, which were constant. He seemed perennially dialed to a nine or ten; used the same tenor of outrage for the ruined mezzorado that he did for the “Blackshirts parading in the street” that he did when his children gave him the overripe pears that they knew he preferred.

“Ah, so you give me your rotten pears! What real jackasses you are!” he’d say with a hearty laugh that reverberated throughout the apartment, then he’d eat the pear in two bites.

So that by the end of the book, I wasn’t just accustomed to Beppino’s insults and shouting, I saw them differently. They were no longer scary but rather emanations of a worried person seeking control. Beppino himself had gone from overbearing to something closer to playful.

Interestingly, here’s what the translator, Jenny McPhee, wrote regarding Giuseppe’s usage of the word “negroism”:

According to Shaul Bassi, the director of the Venice Center for International Jewish Studies, in the Judeo-Italian language of the Venetian Jews, in which Ginzburg’s father was raised, “negro” meant “foolish, awkward, or stupid” and “negrigura,” which I have translated as “negroism,” meant “foolish thing.” Bassi claims that the words never had overtly racial content. Ginzburg, however, was very aware of the words’ racial significance and her deliberate placement of these terms on the opening pages of her novel resonates throughout the book.

I like the idea of cutting Beppino some slack, of him not knowing exactly what he was doing just as much as I like his daughter growing up to be a big-deal writer and holding him to account publicly.

Which is to say that I like reading and thinking about how complicated being a person is.

In the wake of the 2016 election, I posted a selfie of me crying. The caption: This is what a feminist looks like.

I came across it a few months ago and cringed hard. I immediately “archived” it, wishing I could bury the memory, too. But alas, it’s not only still there, it’s attached to another Instagram memory: I remember posting something I’d written on a piece of paper. (This must have been before you could type words in Instagram Stories?) I don’t have a digital record of it, but I know that I wrote something to the effect of how you—that is, the people on Instagram—were helping me cope with the election results much more than my own mother was. (The context was that my Republican mother hadn’t called to offer any comfort in the wake of Trump’s win.)

I don’t know what’s more embarrassing about these Instagram memories: that I was having such an experience on Instagram, that I was having a public tantrum, or that my politics had bled so intensely into my personal life.

Maybe this is another reason I loved Family Lexicon so much. Why I found it so comforting. Peg Boyers puts it best in her afterword:

Politics is never primary in Ginzburg’s world, not even when it threatens to overwhelm private life. The very enterprise of Family Lexicon—the insistent, loving, faithful construction of a family chronicle—may itself be said to be an act of fidelity and resistance.

Giant heart emoji.

I have yet another memory from those days after the 2016 election: I kept Teddy home from daycare. Isaac was nine months old and with me all day anyway, but Teddy was two and a half and enrolled in daycare. I remember taking them both to my favorite bookstore, Vroman’s, and how this one book called to me from the nonfiction shelves. The title: You Must Change Your Life. (It’s a quote from a Rainer Maria Rilke poem, as it’s a book about Rilke’s life as well as the life of Auguste Rodin.)

This memory is much less embarrassing. Because I remember buying that book1 as if it were taking a vow to do exactly that: Change my life.

And well: eight years later, I can at least say that I have. That I did.

I imagine that there are people reading my subdued reaction to Trump’s reelection as a type of complicity or as a renunciation of paying close attention. But I don’t think that’s it. I think I’m just paying attention differently this time around. In 2016, I wanted to understand the other “side” so I could bring them to mine. Because my side was so very right!

But in 2024, I can see how obnoxious that is. How small-minded. What a jackass, what a nitwit I was.

I also remember really enjoying this book.

10/10 (and not *only* for that blurry hockey still omg) 🏆🛵🏆 “…the insistent, loving, faithful construction of a family chronicle—may itself be said to be an act of fidelity and resistance.” Giant heart emoji indeed xoxo

This is 🤌🙌🙏