I don’t know where to start. I’ve abandoned so many essays lately. But I’m making myself finish this one. I guess I’ll begin with winter break.

Los Angeles public schools always give three weeks off over the winter holidays. But since my partner, Matt, has never gotten three weeks off for anything, it never quite feels like a break for me, the stay-at-home mother/writer. At the beginning of those three weeks, I have a keen sense of needing to pace myself. Like I cannot overcommit to activities with the kids because I know I’ll hit a wall.

Which reminds me of one of the essays I abandoned this year. I’d read the book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, which is largely about how the thinking and research around physical endurance has changed.

See, we used to think a person could only run as far or as fast as their body physically allowed them. In layman's terms: that we stop going when our muscles are fatigued. But now, most scientists who study endurance seem to agree that how you feel, whether that’s tired or thirsty or hot or cold or just like you suck at running—affects your performance significantly.

But what I wanted my essay to do was take this concept into the political realm. I wanted to prop up all the science that’s laid out in that book to point out how we’re all biased. How our feelings affect even the most “rational” thinkers1. Even say, the professionals who decide on the headlines at The New York Times! Alas, I got overwhelmed and abandoned it.

But back to winter break. Going into week one, I was feeling pretty good. I’d recently turned in another draft of the book I’m writing to my agent. Plus, my mom was coming to town and renting a house with a pool. And so, the week came and went. I had some time to write, and in it, I began another essay. This one was going to be about how this piece about class politics by Tangle made me want to cry. Why had it made me so emotional? That’s what I was hoping to write about.

But then, halfway through the week, my agent got back to me with her notes on my manuscript. And so, I quickly pivoted. I wanted to pivot.

During the second week of break, on Christmas Eve, we drove up to Big Sur. Our friends have a beautiful place there and had invited us to come. We got there around 3pm. We settled in and then our oldest kid started throwing up.

Which I bring up mostly because one of my favorite memories from that trip was lying in bed next to him on Christmas day while he worked up a sweat in his sleep and I worked on my manuscript. These are always my favorite parenting moments. Being able to do what I want while also being a present parent. Ha.

After a few days of that sweet ocean air and communion with old friends, we came back home. The kids had another week off, but at least Matt would be home for some of it. I worked on my book in the mornings. The kids watched a lot of TV and played a lot of Fortnite. We played sports, too. Sometimes at a skating rink, sometimes in the backyard, and maybe once or twice, at a tennis court.

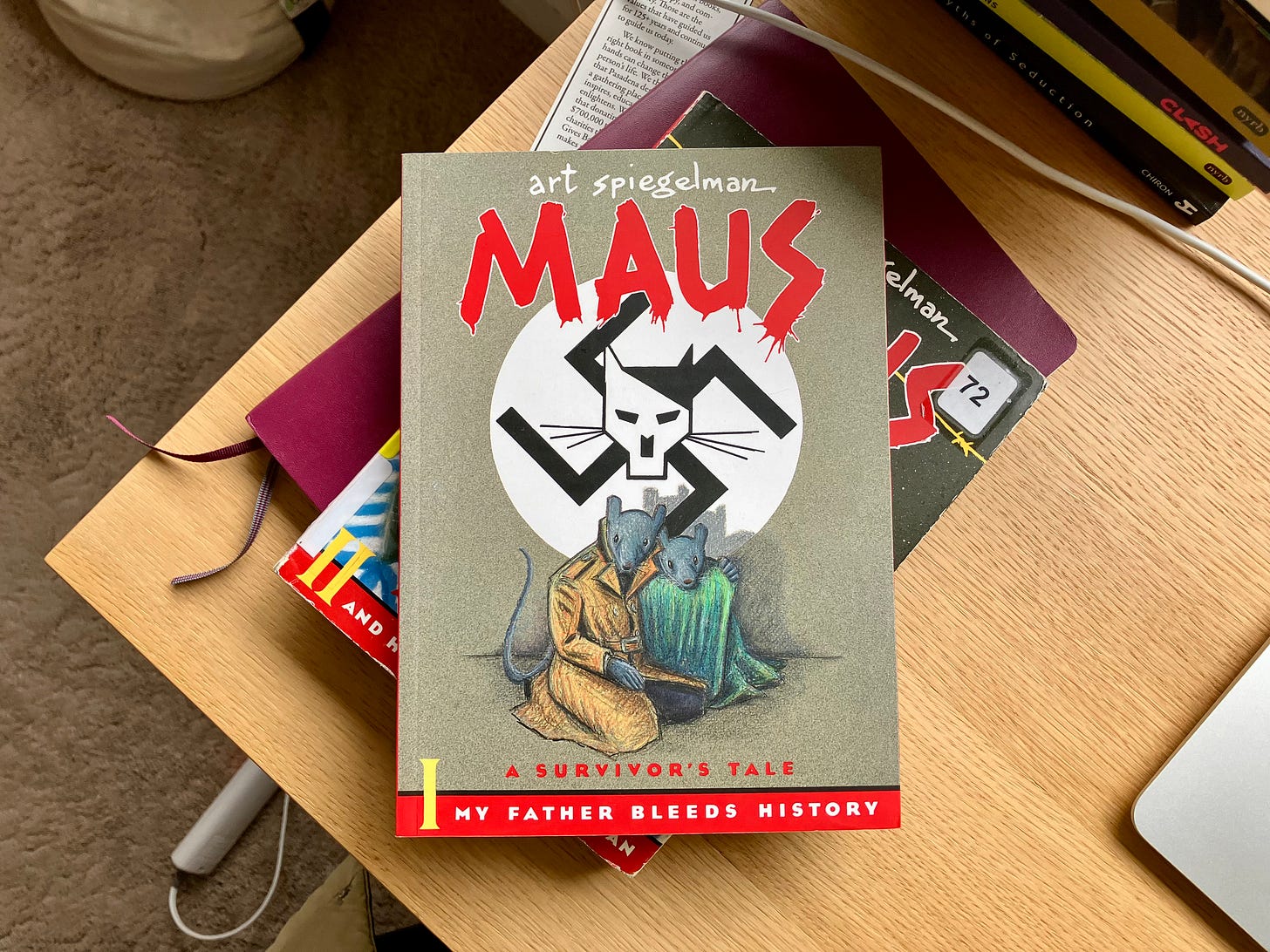

At night, I read. When my mom was here, I’d taken her to Vroman’s, my favorite bookstore, and I’d bought Maus by Art Spiegelman. It’s a book I’d been meaning to read but somehow hadn’t realized was a graphic novel until I was holding it in my hands at the bookstore. I saw too that there was a Maus I and a Maus II. The store was so crowded that I just grabbed the first one and got in line with some of my other selections.

On the very last day of winter break, a Sunday, I baked my younger son’s requested birthday cake. Between this endeavor and a lemon tart I’d felt compelled to make a few days prior because of a surfeit of Meyer lemons on our tree, I felt a real chasm between my current self and the one who used to tackle new recipes all the time. It’s so much work! And then there’s all the cleanup. How had I ever summoned the energy?

The very next day, we sent the kids to school and I felt the relief. “Break” was over! This feeling was tempered by the fact that both the kids and Matt were sad. Break was over. Plus, we had a busy week ahead. There was Hebrew school in Pasadena on Tuesday night. Teddy was starting flag football on Thursday—also in the Pasadena area. And then Friday was hockey, in Pasadena.

But then: Tuesday, January 7th. Our synagogue emailed early in the day saying that in-person Hebrew school was canceled due to the epic windstorm and that they’d send out a Zoom link instead. When I walked to school to pick the kids up around 3:30pm, I wore sunglasses mostly so that twigs and other things that were flying through the air wouldn’t hit me in the eye.

Shortly after coming home, we set the kids up in separate rooms with separate computers for Zoom school. The whole time, I was agitated in a way that felt out of sync with the moment, in a way that felt bigger than the moment. Yes, there was a windstorm. And yes, a fire had broken out on the west side of town. But we were relatively okay.

But then after dinner, we learned that a fire had broken out on the east side of Los Angeles, too. In Pasadena. A group text born during Covid and made up of all Angeleno women was erupting with alarm. The kids became hopped up on our anxious energy. They usually don’t want to sleep together in the same bed, but that night they did with a twitchy kind of glee.

Kind of similar to how I handled election night, I picked up the book I was reading. I was deep into Maus at that point and couldn’t really put it down.

I fell asleep.

In the early morning, when I grabbed my phone I saw I’d missed calls from both my mom and step-dad; they’d seen the fires on the news and were worried. A text from a friend said our synagogue was gone. When I said this aloud to Matt, whom I thought was still sleeping, he said he already knew. He’d been up for a while in the middle of the night. I started texting people we knew who lived near there. They’d all evacuated and didn’t know what the future held. A few hours later, our kids’ school was canceled. This is what the sky looked like from our deck at 7:17am:

I’m not here to list out the tragedies. There are so many. So many people remain displaced. So many kids I know are without schools because they were destroyed.

I think I’m here to tell you about my feelings while all of the worst was happening around us.

It felt like Covid all over again: our kids’ school canceled suddenly and without a plan. The air was horrendous and so, like Covid, we were all stuck inside together. (After having been together for three weeks already, remember?) Our dog was sprinting around our three-bedroom floor plan. His claws slipping on the hardwood. Local friends were texting out information. Which apps to download. Whose houses had burned. Everything was closed. With a mask on, I tried to go to the library, which was stupid because of course it was closed.

Do you know about this psychological pattern—how when you’re living through something difficult, you have to just get through it. And so sometimes (most times?) you don’t let yourself feel certain feelings. Because they’re not helpful to your survival of the event?

This is the only way I can make sense of my retroactive anger. Because being stuck at home with the kids again, watching the people around me try and make the best of the worst situation again, feeling helpless in the face of government closures again, it really made me, well: pissed.

Our public elementary school had shut down for Covid almost five years ago exactly, but in my body, it was like it was yesterday. I was newly angry about it. About how long they stayed closed and how hard that had been. When friends left town five years ago because they could. Because they had access to second homes, I was jealous but supportive. But now, when these same friends skipped town to breathe better air, I threw my hands up in the air. I was so annoyed. “Of course!” I complained to Matt.

I think it was Friday when we looked at the air quality map and then did a search for an Airbnb where the air was better, but it was like trying to shop for toilet paper in March of 2020. The only places available did not look inviting and bonus, were way too expensive.

Next I was mad at the people in my life who don’t live in Los Angeles and hadn’t checked up on me. Were we all so siloed that they hadn’t even noticed what was happening to our city, to my family? But when I went to The New York Times or CNN, Los Angeles was the top headline. Did they not read the news? Did they not understand that we were suffering? What about their social media feeds because mine was: FIRE, FIRE, FIRE.

But simultaneously, I was thinking about Maus, the subtitle of which is “A Survivor’s Tale.” I’d finished the first book by then and had moved on to the second.

I assume the book first entered my consciousness a couple of years ago when it made headlines for being banned in a Tennessee school district. And with the cover looking like how it looks, I understood that it was about the Holocaust, but that was it. So it wasn’t until I started reading that I realized it had come out a long time ago. According to the inside flap of Book I, the first six chapters had originally appeared in Raw magazine between 1980 and 1985.

As previously mentioned it’s a graphic novel, though I would more accurately call it an illustrated memoir. The only thing fictional, it would seem, is that all the Jews are drawn as mice; the Nazis are cats, and so on. The author and illustrator, Art Spiegelman, is a main character, and it’s set in the late 70s when Art is an adult—around thirty-years old—and seemingly newly interested in making a book about his father’s story of having survived WWII and specifically Auschwitz.

At first, I wondered why Spiegelman had set it up like this with himself as a character. Why not just focus on his father’s story straightforwardly without going back and forth between present day and past? The drama is in the past, I thought. Why not just focus on Vladek? But having read both books now, it’s quite clear why he did it the way he did.

Because so much of the drama, the heart of the book, is the father-son relationship. It’s in Art’s attempt at making sense of something nonsensical, of trying to put back together something that will always be broken. It’s in the way that by the end, as a reader, we can see that yes, Vladek—his father—had made it out alive. “But,” as Art’s partner, Francoise, says in Book II, “in some ways, he didn’t survive.”

Along the way, Maus disabused me of notions I’d been subconsciously carrying.

One is about Good Samaritan non-Jews I’d heard about who went above and beyond to hide Jews during the war.

Vladek’s journey is so long and windy, but at one point he and his wife are being hidden by such a person, a German woman. Vladek meets her at the black market. This woman knows they’re hiding in a barn, and so she invites them to stay with her in her house. She explains that her German husband rarely came home from where he was stationed. But then Art interrupts his father by asking, “You had to pay Mrs. Motonowa to keep you, right?”

Vladek responds in his heavily-accented English: “Of course I paid… and well I paid. What you think? Someone will risk their life for nothing?” He goes on to explain how he paid for the food she gave them too, and how one day, when he didn’t have enough cash for bread—he had to exchange valuables for cash—on that specific day, Mrs. Motonowa said, “Sorry… I wasn’t able to find any bread today.”

Old Vladek tells Art: “Always she got bread so I didn’t believe… but still, she was a good woman.”

I don’t bring this up to shame this German woman. I bring it up because the version of this story that lived in my head—the one of non-Jews helping out Jews was rosier, less transactional, more Schindler’s List-y. I’d never considered that Jews were paying to be hidden and fed. But of course. That German woman was also trying to survive.

A little bit earlier in the timeline, after Vladek was drafted into the Polish army, captured as a prisoner of war, and escaped, he and his wife are caught by the Germans. They’re rounded up in a room with about 200 other Jewish prisoners. Once a week, a portion of these Jews were sent to Auschwitz. But from the window of the room they’re in, Vladek sees his cousin—a member of the Jewish police—in the courtyard. Vladek yells and waves until his cousin looks up. With signals, he makes it clear that he’s asking for help and that he can pay.

Here again Art interrupts his dad with a question: “Wouldn’t they have helped you even if you couldn’t pay? I mean, you were from the same family.”

“Hah! You don’t understand,” Vladek says to Art. “At that time it wasn’t any more families. It was everybody to take care for himself!”

This is the line that spoke to me when I was having a mini tantrum about friends of ours who had managed to get out of town. Everybody was taking care of themselves with whatever means they had to do so. Of course they were! If we had a second house to go to or if we’d reacted more quickly, maybe we could have gotten out of town too. (I was and remain annoyed by this post by Miranda July though.)

Please note: I’m not trying to make a direct comparison between surviving the Holocaust and surviving the Los Angeles wildfires. What I’m trying to do is relay how in this specific milieu in which I find myself (hipster affluence, let’s call it?) I feel so acutely this overemphasis on the ethics of survival—myself very much included!—versus the actual horrors of survival. So much so that some universal sympathy has been lost.

“Worrying about budget, sales figures, traffic and whether the heat will let up seems trivial,” James Hollis writes in On This Journey We Call Our Life.

And surely it is, but compared to what? Suffering is relative, contextual and very, very personal. The great suffering of the dispossessed is so immense that most of us who live privileged lives have to turn away in order to be able to conduct our banal, quotidian lives.

In other words: Let’s all give each other space to mourn our tiny and gigantic losses. Yes?

But I think the biggest Maus-induced epiphany I experienced arrived toward the beginning of Book II. In this second installment, we see Art struggling at his drafting table. Curiously, he’s not drawn as a mouse but as a human wearing a mouse mask. In this timeline, Book I has been published and to huge critical acclaim. But also: Vladek has died, and Art is having a hard time writing anything. We see him walking to therapy.

His therapist is a kind of peer of Vladek’s. His name is Pavel. He’s “a Czech Jew, a survivor of Terezin and Auschwitz.” In their therapy session, Pavel is also wearing a mouse mask. He asks Art if he admires his father for surviving.

“Well…sure,” Art says. “I know there was a lot of luck involved, but he was amazingly present-minded and resourceful…”

For the entire first book, I thought this too about Vladek. I was so impressed by him. And would continue to be in Book II as his story continues, having already told it all to his son before he died.

But here Pavel says the real zinger. He says, “Then you think it’s admirable to survive. Does it mean it’s not admirable to not survive?”

I love Art’s response: “whoosh,” he says. “I-I think I see what you mean. It’s as if life equals winning, so death equals losing.”

“Yes,” Pavel says. “Life always takes the side of life, and somehow the victims are blamed, but it wasn’t the best people who survived, nor did the best ones die. It was random!”

But having gone through everything Vladek went through, how could Vladek not think that? How could he not attach meaning to all that suffering? It’s at this moment that the mouse masks make sense as well. Art hasn’t suffered like his dad suffered. So what does that mean?

It’s so silly when you break it down and say it aloud: that going through something incredibly difficult doesn’t automatically make you a more worthy human. That being oppressed, historically or otherwise, isn’t a surefire path to sageness. And yet, how often in my life have I believed this? How often have I felt, especially as a writer, that I can’t disagree with someone because I didn’t go through the exact same hardship? Like they’d come out with a level of wisdom I could never access.

It’s all so tricky because of course going through something incredibly difficult is how we grow, is an opportunity to become larger. But, like Vladek, we don’t have to. We can also be destroyed by our hardships.

Most people don’t want to go through a life-changing experience. Talk to someone in the middle of a crisis. A cancer diagnosis, or deep depression, or their house having burnt down and yet they still have a mortgage to pay while also needing to find a new place to live in an insanely overcrowded market. One hundred bucks says that if given the choice to press a button and not go through any of these experiences they would hit that button.

It reminds me of the ending lyrics of that crushing Phil Elverum song, “Real Death” which is about the death of his wife from cancer. Of her being permanently gone, of real death, he sings: “It's dumb. And I don't want to learn anything from this.”

Exactly.

Every New Year’s Eve, Matt and I make a list of the top ten moments of the year, and then we present them to one another. It’s usually fun, especially to see what’s on his list that didn’t make mine and vice versa. We’ll sometimes have a drink and reminisce while we read them off.

But this year, I didn’t want to make one. I kept saying to Matt that nothing good happened in 2024, so why bother? I don’t think I even had anything specific in mind. It was just a feeling. That it had been a bad year. But Matt wasn’t taking me seriously. In the days leading up to January first, he kept saying things like, “I can’t wait to see your list!” and “I’ve been working on my list!”

So, begrudgingly and like a child, I sat down and finally started mine.

I began scrolling through my phone’s photos, starting in January and working my way up to the present. (Usually you take photos when you’re happy, having fun, or at least doing something interesting.) But my heart wasn’t in it. I’d write something down and then add a question mark after it. I was just trying to get to ten.

And I did.

But then, before I closed my journal, it dawned on me that maybe this year’s best moment wasn’t captured on camera. That maybe it wasn’t a moment at all, but an accumulation of many.

Thinking of this, I wrote down the number eleven and then started listing things I’d done all year that made me feel good about myself. These things were boring. They are boring. Some of them, e.g. “working on my book” are things I’d done almost daily. They were steady commitments I’d made to myself and that held me in place when the world hadn’t made any sense.

But when I “presented” my list to Matt, I didn’t read off number eleven. Instead, I described it. I described why I thought this year was different than previous ones. And what I ended up describing was a year of loss. Specifically, I’d lost my ideology. I’ve written about this before on here, but what I failed to mention is how hard this has been. To argue with close friends. To read the articles they send me and disagree with the very premise. The slant of them. To risk myself by speaking up when people say things that I’ve found offensive. To spend hours drafting “Letters to the Editor” to The New Yorker that they never responded to.

As I said all this to Matt, I realized that something had been gained through all of this, too. That though I struggled all year and very often felt betrayed by my own people, that some part of me was grateful for the experience. Here’s James Hollis again:

Recall the betrayal of Job discussed in a previous chapter. The experience of betrayal is perpetrated as much by our own naivete, our insufficient apprehension of complexity, as it is by the other party. Though it is painful, that complexity serves to enlarge the personality.

To quote Art Spiegelman here: whoosh.

What Hollis is saying in the above feels incredibly true to me. Back when I had my ideology, things were so much simpler. Pain and oppression equaled sources of righteous wisdom. Rich people were easy targets. When my ideology was shored up, I subscribed to The New York Times and The New Yorker and that was it. Done. Now I have so many subscriptions! I get The Atlantic now. I pay for Tangle in order to get their Friday edition. Sometimes I’ll read an article in The New York Times and then click over to The Wall Street Journal and see how they covered the exact same story. (Very interesting activity, I might add.)

In short, why did this year feel so bad? Because it was a growth year.

Thanks for being here through it all! Looking forward (I think) to find out what’s in store for 2025.

There’s even a word for this.

Your writing always makes me rethink things Amelia. I get a little dopamine hit when I see your substack in my inbox.

2024 was a year of ideological rugs being pulled out from under me too. Not sure if there was much growth, tbh. But I keep coming back to something Ezra Klein said in a podcast recently: that Twitter makes him dislike people he likes, and podcasts make him like people he dislikes. I’ve been coming back to this when my nervous system gets flooded with rage at something- what kind of engagements open me up to people? How can I feed those? How can I move through the world in less cortisol-spiked ways? It’s humbling to lose certainty, but humility can keep us grounded.

Disclaimer: I just read this and then re-read 2 other essays you wrote, so I’m not quite sure what I’m responding to. I love the thoughts on Maus.

Lovely. I get your struggle.

And I get the frustration with everything being so damn random.

And the frustration (and HUBRIS) when you find out someone you love doesn’t love music, or meditating, or Maus. Grrrrr